The Prehistoric Giants of the Sky – The Azhdarchids

By Jackey Lu Y12

Azhdarchids are the Cretaceous's giant flying storks (long-neck wading birds with long heavy bills). Plenty of articles about them had been written, especially about the record-breaking pterosaurs, the largest of which managed to stand at giraffe height, towering over all in its ecosystem (except some of the sauropods). Now, not all Azhdarchids are that giant, but even so, their popularity seems only to be restricted in the paleontology community. Thus, this article is just an introduction to these magnificent and regal animals. I know I fell in love with these elegant creatures from seeing Mark Witton’s paleoart on them. We’ll cover a little everything about them.

Growing Pains

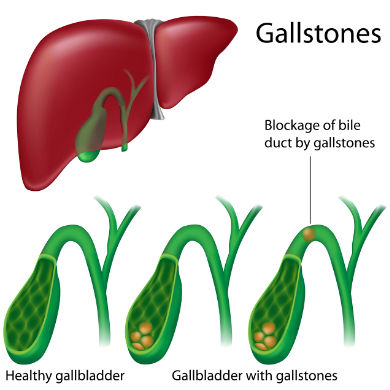

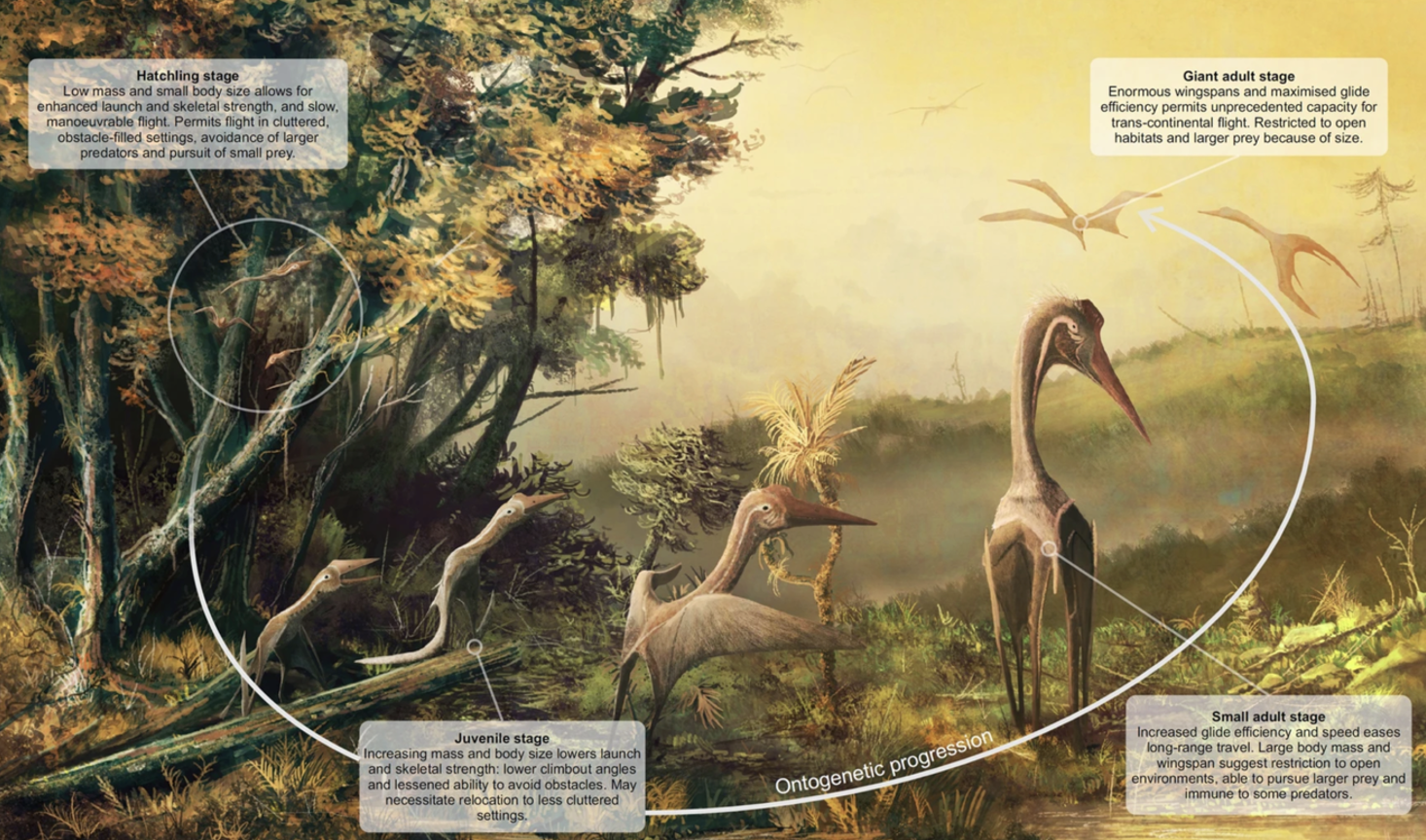

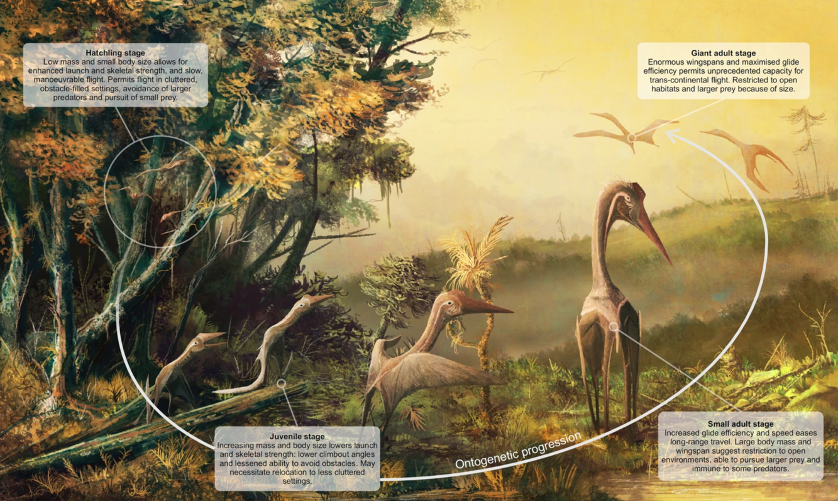

With Mark Witton being one of the most active paleontologists and artists who engaged in generally more forms of casual writing (and just for being an approachable and funny British chap), they are the extensive materials available for talking about Azhdarchids. Included in them is detailed research with a published paper for Azhdarchid ontogeny. Thus, feast your eyes on the brilliant infographic below.

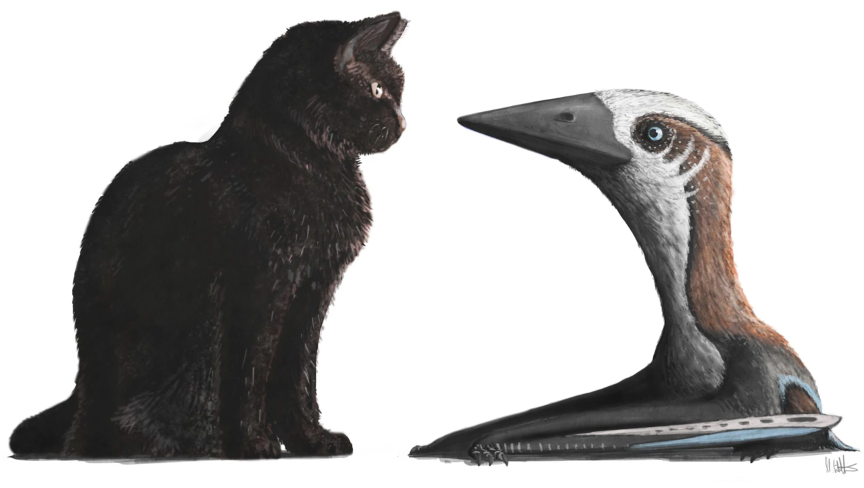

Though the massive adult size of these pterosaurs would allow them to wander in the cretaceous fields very much unmolested, they started as small hatchings. The small hatchings would have spent most of their time in the trees, honing their flying skills and preying on the smaller critters living in the woods. Here, another thanks to good old Mark Witton, because of whom we could visualize how big an average young Azhdarchids look like…

Once they reached considerable size (usually at the juvenile to sub-adult stage), the Azhdarchid pterosaurs would leave the forests and start moving to nearby clearings. Now in the open, they would start to fully take advantage of their walking proficiency to spend more time striding the prehistoric clearings. There’s not that much information on the growth rate of giant Azhdarchid pterosaurs, they would either slowly plod their way to the giant adult size or see exponential growth in the sub-adult stage to reach their full size. After growing into their adult forms, the Azhdarchids would become a wonder in their ecosystems.

Taking to the Air

Referring to the concurrent pterosaur research, all pterosaurs (including these giant murder storks) would utilize the launch method called ‘quad-launching’ to take off from the ground. Much like modern-day bats, this process involves these animals pushing hard against the ground with their strong forelimbs and engaging their wings to flap, while in the air, to become fully airborne. We need to rid ourselves of old conceptions that suggest these animals rely on winds to fully take off. These are active, well-muscled, warm-blooded animals that are completely capable of powered take-off and flying on their own. At the same time, hollow bones, aerodynamic torso, and wings are structures that also help to carry these giant animals into the sky.

Their Paleobiology

Paleontologists had spent quite a long time trying to figure out where azhdarchids fit in their local ecology. Originally, it was proposed that these animals are derived skim feeders, specialized in soaring over the seas to catch large fish. However, skim feeding is an outdated theory for pterosaur feeding speculation in general. Especially so for the azhdarchids, as their jaws can't support the immense stress that skim feeding would cause. Recently, in substitution, another speculation that suggests a more terrestrial lifestyle was proposed. The terrestrial models state that these animals would wander the expansive coastline and utilize their long tweezer-like beaks to pick up any small animals on the ground.

The most current and agreed-upon model of these giant pterosaurs suggests that pterosaurs were adapted to walking and long-distance flights using these structures. They would use their abnormally long legs to stride their way to shorter distances and utilize their wings when they wish to travel further. In terms of the animal’s diet, the current consensus is that they would swallow anything that they could fit down their oesophagus. When larger bodies were found during scavenging, their thin long beaks could be used to take pieces off with accuracy. Most of the time these pterosaurs are not suspected to hunt down large animals in their habitat but would feed themselves through scavenging or catching smaller prey that could be swallowed whole.

The Pecking Order

So, we have established that these animals are giant murder storks of the Cretaceous, and they are capable of intercontinental flight, meanwhile gorging themselves on anything they could get between their beaks. The natural next question is: what was their niche in their ecosystem? The peculiar niches of azhdarchids may be best explained through a case study. Thus, enter stage left, Quetzalcoatlus!

If you are a paleontology nerd then you might know that there are two species of Quetzalcoatlus, Lawsoni and Northropi, with the latter being the giant one. For Lawsoni, whose remains are found in the Hell Creek Formation along with other bone beds, we knew that it had a more passive role. It would have scavenged from the bodies left by the other major predators in the region like Tyrannosaurs and perhaps even Dakotaraptor, whilst also feeding on other small mammals and juvenile dinosaurs of the region. Quetzalcoatlus Lawsoni is in no position to compete with the larger therapods like Tyrannosaurus but should see no problem in contesting a body or two from Dakotaraptors or other similar-sized animals.

Quetzalcoatlus Northropi, on the other hand, is much more intimidating with its larger size. While it can’t challenge the status of Tyrannosaurus as the apex predator, since the pterosaurs are quite thinly built, it does pretty much tower any other carnivore in its habitat. Medium-sized animals would have simply squabbled away from the sight of these things landing in front of them, and in the context of Quetzalcoatlus Northropi, smaller predators like Dakotaraptor would have also been on the menu.

By this point I’m sure some of you are asking, is there somewhere, anywhere on Earth that azhdarchids are the apex predators of the region? Well, for that we’ll have to go to Romania!

Romania right up to the end of the Cretaceous mass extinction was a series of islands, as the whole of Europe was somewhat submerged at that time. Animals on the islands were all downscaled, smaller versions of their relatives on the mainland. Even though these islands are separated by vast bodies of water, this would be no challenge for large azhdarchid pterosaurs to cross. Hatzegopteryx Thambema was the uncontested apex predator of the region. They would simply island hop to prey on dwarf sauropods and gnome hadrosaurs. Compared to the other two named giants, Hatzegopteryx is considerably stockier than the other two: It is so robust that the original material found in the animals was perceived to belong to a giant theropod dinosaur.

Pop Culture Appearances

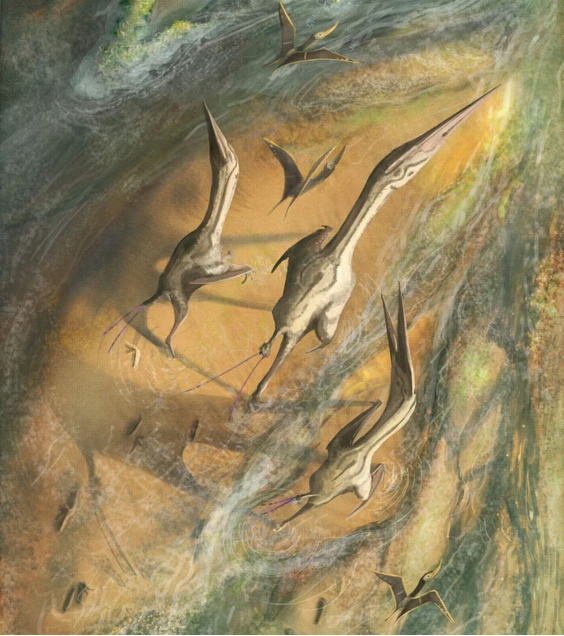

As of writing this article, azhdarchids are missing love from the wider public. Yes, a few articles by news agencies here and there about giant pterosaurs eating dinosaurs sure get the clicks, but these animals have not really entered the public consciousness. Though saying that things are shaping up to take a turn for the better as high-quality documentaries like Prehistoric Planet (above image is prehistoric planet’s depiction of Hatzegopteryx and speculative mating rituals in season 2) do shine a light on a variety of azhdarchids, Jurassic World 3 also jumped on the bandwagon in introducing Quetzalcoatlus to the franchise--though it could be argued whether that inclusion had caused more misconception.

Problems still arise, as many other taxa that are less well known but just as interesting are left undepicted or underrepresented, even in the paleontology community. However, a lot of it was due to the animals being too fragmentary to name. But the consensus is that Quetzalcoatlus Northropi and Hatzegopteryx Thambema were the two main giant pterosaurs. This left out the third named giant known to science Arambourgiania Philadelphiae which is shown above. But all in all, the future is looking bright for these giant flying reptiles as higher quality media and papers are released about them. Plus, as any esteeming paleo-nerd, honestly, can you really resist a giant stork, like Pterosaur?

Acknowledgment

All artworks are from Mar Witton